Wednesday, when I took the train out to West Orange, New Jersey, the mist hanging in the Orange Valley made it seem like Ireland. My second cousin (my dad’s cousin), Bill, had arranged a tour focusing on sites key to the family history of my paternal grandfather, whose father was involved in hatmaking at a time when the nation’s hat factories and companies were centralized in the Orange Valley and in New York. As I stood in Penn Station, Wednesday morning, and waited for the train to Newark Broad Street, I absently listened to the New Jersey Transit voice announce departing trains:

“Now boarding on Track Four, the North Jersey Coast Line, calling at Secaucus, Newark Penn Station…Change at Long Branch for Elberon, Allenhurst, Asbury Park, Bradley Beach, Belmar, Spring Lake, Manasquan, Point Pleasant Beach…”

My dad grew up in Spring Lake, and was often in the city on his own and with his family. It’s a rare week when I don’t hear a reference to somewhere he would have been, or where my grandparents would have been. But it is rare to be visiting haunts of my great-grandfather and great-great grandfather.

The immigrant and pioneer ethic runs strong in my family, as it does for many. Now, however, I think that nineteenth-century ancestors would no more recognize us twenty-first-century folk as kin than they would Martians. As the train clanged its way out of Penn Station and over the marshes, all I could think was, They worked harder, had less, and did more.

Bill met me at the Highland Avenue station, and pointed out the view west: the Orange Valley sloped up, through a series of foothills, into a green crest that disappeared in the fog. It’s no doubt the mark of an amateur family historian, but I can’t help but look at Bill and think how much he looks like my grandfather and father, with that familiar long, calm face.

“There’s a surprise at the end of the tour,” he told me, walking down the steep staircase from the station. I’d already been surprised by how extensive Bill’s research has been (though I’m not sure why; lawyers are world-class detectives, and Bill’s genealogical skills are astounding). “I think you’ll–.” He stopped and smiled. “Well, I think you’ll enjoy it.”

We walked down Freeman Street to Valley Arts, a community center tucked inside a former storefront. A table of dark computers lined the wall, and a woman was wrestling a giant framed map onto a table nearby. She propped it up against the wall, steadied it, and dusted her hands off on her jeans, with a laugh. Karen Wells is the town historian and a woman of formidable memory.

“From 1904 to 1911,” she said, “there was so much building here it was almost like a new city.”

A crowd appeared at the doorway and poured in: Curtis, Allan, and Andrew, from the HANDS community redevelopment organization; Bill’s brother Mike (who looked like my uncle) and his wife, Kay; and Bill’s wife, Jill. As introductions went around, Bill pulled out folders and copies of nineteenth-century and turn-of-the-century maps, and proceeded to lay out a marvelously detailed itinerary, with a list of sites, addresses, and dates.

Karen, Bill, and Kay leaned over the 1911 map of Orange Valley, hunting for family addresses, while Mike settled into a chair.

“You know,” Mike told me, massaging his knee, post-knee-replacement surgery, and reading the streets listed on the itinerary, “Shanley Street–Bernie Shanley was President Eisenhower’s appointment secretary, and he was a tyrant! He treated all of the Irish very badly, though he was Irish.” When I looked at Mike, his profile was that of my uncle’s, and his voice was very much my grandmother’s (though on a different side)–passionately Irish. Being Irish-American in California and Colorado is something slightly different than being Irish-American in New York and New Jersey. Entire groups of men look like the men in your family; women with ivory skin and high, wavy hair shock you at how much they resemble your grandmother.

Around the turn of the century, there were about sixty different hat manufacturing companies in the region. My great-grandfather started out here, working in various hat factories for a couple of years before he became a bookkeeper in the head Orange office and, shortly after, in the New York subsidiaries, where he became the president.

To start the tour, we walked down Mitchell Street to what was originally the Stetson Hat Factory–renamed the No-Name Hat Factory, Bill said, shaking his head, after a family dispute among the Stetsons. Before we went inside the abandoned building, Andrew paused and looked at us.

“Folks, please understand that the building has been out of use for a long time,” he said. “So watch your step.” As the first of us went inside and up the concrete stairs, he called, “We do have disinfectant spray for your shoes, when you’re done!” I put aside my mortal fear of bedbugs and picked my way up the staircase, which was littered with old paint flakes and sodden ceiling-tile insulation. Wearing ballet flats on a genealogical expedition? Another clear sign of an amateur. I stepped in and through piles of old wood and books (Books! How could people leave books behind?), and over toppled desks and piles of molding papers that had long since fused together.

![6Inside No-Name [formerly Stetson] Hat Factory 6Inside No-Name [formerly Stetson] Hat Factory](https://accidentalimmigrant.files.wordpress.com/2009/06/6inside-no-name-formerly-stetson-hat-factory.jpg?w=300&h=225)

It’s hard to understand what people leave behind, or why–but it is compelling.

Andrew pointed out that a furniture maker had worked on the second floor until not too long ago. And, he added, as we crowded into the room, a recording studio had occupied the third floor of the factory until a few years ago.

“The song ‘Juicy Fruit’ was penned here,” he said, smiling. “It was a monster seller–written by the songwriter Mtume.” (James Mtume wrote for, among others, Roberta Flack.) “Juicy Fruit” was immensely successful on the R&B charts in the 1990s. The incongruity of a nineteenth-century hat factory transformed into an R&B studio made me smile. One of the walls was covered in Sharpied signatures from the floor’s songwriting era. Everyone agreed that the wall had to be saved.

HANDS, Inc. (Housing & Neighborhood Development Services), a non-profit focusing on revitalizing neighborhoods in Orange and East Orange, wants to preserve and repurpose many of these old factories. Andrew and Karen emphasized that, structurally, the buildings were still very sound and have features (like high-ceilinged rooms) that lend themselves to loft-style residences, or to retail.

It was strange to be walking in a building where, presumably, my great-grandfather had spent time working. Since all that was left of the hat factory was the building itself, though, it took a lot of imagination to picture him striding through the rooms.

The seven of us made our way to the rooftop of the building. Bill walked out first on the tar-papered roof, which sloped down to the center of the building; Jill looked apprehensive. Mike wisely stayed in the doorway and took photos with his cell phone. Far off to the right was a person-sized hole in the roof. The view west from the rooftop was of the tree-crammed opposite slope of the valley. Few houses poked through the greenery, but off to the south, on Valley Street, was Our Lady of the Valley Church, where my great-grandfather’s family would have gone to Mass. My great-grandfather’s older sister attended the church school, which was established in 1882, and became a nun in the parish-run convent. To what degree is it a reflection of the lack of opportunities for women, and to what degree did the decision reflect her interests?

Valley Arts’ Karen Wells in front of the No-Name Hat Factory building, holding artifacts from inside.

“I’ve always been interested in history,” Karen said happily. “When I was a kid, they couldn’t give me new toys; they had to give me old ones. Buildings speak to me.”

It looks like the Stetson Lounge is still a functioning bar, though it was quiet on a Wednesday morning, and the door was shut.

Stetson Street is a tiny lane of what was once employee housing. The row houses are small, and bunch up against each other like shoes in an apartment hallway. As we stood there at the edge of the street, a white-haired woman in a housedress stepped tentatively out on her porch, one hand on the screen door, and shaded her eyes, looking down the street at us. Someone waved to break the tension. After a moment, she waved back and smiled.

The sheer expanse of the second building we explored, the F. Berg Hat Factory, was impressive; it had been the biggest hat factory in Orange. On one of the empty floors, we looked up at the rafters–heavy beams that looked as though they could have been used for shipbuilding.

“That’s still solid,” Karen remarked. Orange was known for its old-growth trees, she explained, and many of them went into nineteenth-century factory construction in the region.

HANDS hopes to redesign the F. Berg building as studio and retail space; since one floor housed an abandoned studio, it seems like the building will be happy with that.

We stopped at the newly reopened three-table State Diner, on Valley Road, for lunch. The Kullman diner was built in the 1950s and originally stood in Bloomfield, New Jersey. It was moved to its current location in the ’60s, and (according to the menu) the owners are rededicated to bringing it back to its original glory as a Jersey Diner.

Everyone ordered a sandwich–Kay added, “Go heavy on the mayo,” with a grin, to her order–and I was amazed to find out that a Sloppy Joe in New Jersey is a sandwich with coleslaw inside. Who knew?

After lunch, we piled into one car and went in search of the Newark points on Bill’s itinerary. The first stop was the cemetery, where I looked down at the small headstone for my great-grandparents and a baby that had been lost, early on. The letters in my great-grandmother’s name were still strong and clear, etched in bold black contrast on the granite. My great-grandfather’s name was faded, nearly slipping off the top of the stone; he had died nearly forty years before she had. But the curve of the “J” was familiar.

Parts of Newark looked like nothing I’d seen in American cities. (Israel, yes.) Denver has its run-down sections, but (in my mind, at least) they don’t have the desperation and poverty that seems to stretch for miles in Newark. Driving from the cemetery, we passed turn-of-the-century buildings–whole blocks–with elegant columns and architectural work that belie the dire conditions current residents face.

“There’s no right way to do something wrong,” Kay read slowly from an announcements board outside the West Side High School, as we passed by. “That’s not a good sign.”

We stopped at two churches toward the end of the tour: St. Columba’s Church (built in 1897), where Bill’s father (my grandfather’s brother) attended grammar school.

“San Columba?” someone exclaimed incredulously as we pulled up in front of the church, a brick building on a curved corner of the street, with a sign outside that read “San Columba.”A woman in the church office said that the congregation was now predominantly Spanish-speaking.

The church is small, with pews squeezed in around the altar, and (according to the church web site) was built around 1897 in Renaissance-Revival style for a booming Irish-American parish centered around Newark’s Lincoln Park neighborhood. The campanile is visible for blocks. When the family moved to Newark, the walk to this church would have been only a few blocks, and we drove by the street where they lived, before continuing on.

The last point on the tour, Blessed Sacrament Church, was the most exciting, Bill promised. He had been on the phone throughout the afternoon, trying to contact someone at the church to let us in. When we pulled up next to the church, the gates were locked and there was no answer at the rectory door. Finally, a woman with graying hair, glasses, and a calm gaze walked out from a side door. Janice Champ was a lay minister in the church, and happily waved us in through the basement, where a man was running the waxing machine over the linoleum. We filed down the ramp, up one level, and edged past the altar.

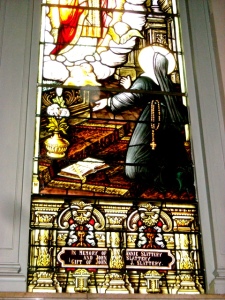

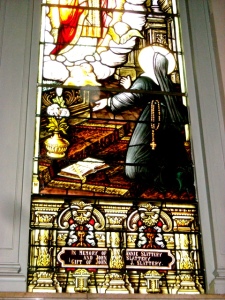

At first, I didn’t notice anything particularly different: the group walked down the aisle, browsing the stained-glass windows. Then, at the end, one came into focus.

Blessed Sacrament was built around 1912-1913, and my great-grandfather would have donated this window in honor of his parents at a time when he had become president of a number of hat factories and subsidiaries in New York and New Jersey–a substantial psychological distance from the hat factories and close quarters of West Orange. Bill speculates that the saint pictured is Mary Margaret Alcoque, patron saint of lost parents.

A set of basic questions underlies most genealogical research: Who were they? What kind of lives did they lead? When were they happiest, and saddest? What changed their lives? What are their stories? For this side of the family, this one day in New Jersey went a long way toward linking together some of the answers.

![Reblog this post [with Zemanta]](https://i0.wp.com/img.zemanta.com/reblog_e.png)

![6Inside No-Name [formerly Stetson] Hat Factory 6Inside No-Name [formerly Stetson] Hat Factory](https://accidentalimmigrant.files.wordpress.com/2009/06/6inside-no-name-formerly-stetson-hat-factory.jpg?w=300&h=225)